Enjoying Communication at the Kyoto International Manga Museum

Recently I went along to the Kyoto International Manga Museum (MM), which, apart from a new building, occupies an old elementary school previously attended by local children. The stout concrete walls and wooden floors and doors give the museum a uniquely imposing and warm atmosphere. The outdoor space, where visitors sit or lay sprawled out reading their favorite comics, used to be the schoolyard where children boisterously played. Of course, everyone can enjoy the MM just as they like, but here I would like to introduce some participatory activities in which visitors, including an increasing number of foreign travelers in recent years, can enjoy communication with the museum and among themselves.

Kamishibai Performances

Kamishibai Performances

(2F Kamishibai Room)

When I entered the Kamishibai Room, I was amazed by how lively the participating children were. I say “participating” because the kamishibai performances (sliding-picture storytelling shows) are a two-way, truly participatory form of entertainment. One of the museum’s kamishibai performers, Yoshitake Araki (aka Rakkyomu), gives shows of about 30 minutes. His shows consist first of all of a quiz using kamishibai pictures and then, depending on the response of the audience that day, either traditional and well-known kamishibai, such as Ogon Bat (Golden Bat), or a new kamishibai that he has created himself.

In the quiz, for example, Rakkyomu shows a picture momentarily and then asks the kids how many penguins were in it. The children are all eyes and ears, and hands shoot up. (Indeed, the children are so attentive, I was told that sometimes schoolteachers come along to observe the show and learn some lessons!) “3!” “More than that!” “21!” “Too many!” “8!” “Not far off!” “10!” “Right! Well no, actually it’s the number between 8 and 10.” “I know! I know! I know!” Rakkyomu points to a little girl who had given the wrong answer once and lost confidence. This was an easy question, so he was giving her the chance to get her confidence back. “Okay, the girl over there . . .” “57!” “Why on earth 57? I told you it was the number between 8 and 10, didn’t I?! Still, that’s so crazy, you deserve a prize!”

After the show, I asked Rakkyomu about his approach. “That little girl just now was shy, so I wanted to give her a bit of confidence,” he said. “But it didn’t work, did it? [Laughs] This isn’t school, though. If the others find it funny, it doesn’t have to be the correct answer.” Rakkyomu wants to draw out the children’s individuality and give everyone a good time. “But sometimes there are interfering kids who try to steal the show. It’s rather painful to watch, actually. I guess their parents just don’t ordinarily give them much attention.”

After the show, I asked Rakkyomu about his approach. “That little girl just now was shy, so I wanted to give her a bit of confidence,” he said. “But it didn’t work, did it? [Laughs] This isn’t school, though. If the others find it funny, it doesn’t have to be the correct answer.” Rakkyomu wants to draw out the children’s individuality and give everyone a good time. “But sometimes there are interfering kids who try to steal the show. It’s rather painful to watch, actually. I guess their parents just don’t ordinarily give them much attention.”

At the peak in 1950 there were about 50,000 kamishibai performers nationwide, but by 2008 the number had dwindled to around 20. Rakkyomu, who chose this path as his calling, was born in Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture. When he was young, he wanted to become either a manga artist or a comedian. After graduation from university he went into agriculture, where he noticed that people’s lives depend a lot on others and the things around them (including agricultural crops). That was why he decided to become a kamishibai performer—to come face-to-face with children and draw out their potential.

Recently the number of foreign visitors to the museum and kamishibai shows has been increasing. This time I met two visitors from Australia, Nataliia and Ilya. Nataliia spoke good Japanese and could just about understand Rakkyomu’s rapid-fire Kansai dialect, so she laughed a lot during the show. Ilya did not know Japanese so well and found the language in the kamishibai rather difficult, but nevertheless he seemed to have enjoyed the emotive and rhythmic storytelling. Nataliia and Ilya are studying Japanese in Kyoto for one year, after which they will think about what to do next. They learned about the manga museum on the Internet. I’m sure they will come again to read manga and study Japanese here.

Recently the number of foreign visitors to the museum and kamishibai shows has been increasing. This time I met two visitors from Australia, Nataliia and Ilya. Nataliia spoke good Japanese and could just about understand Rakkyomu’s rapid-fire Kansai dialect, so she laughed a lot during the show. Ilya did not know Japanese so well and found the language in the kamishibai rather difficult, but nevertheless he seemed to have enjoyed the emotive and rhythmic storytelling. Nataliia and Ilya are studying Japanese in Kyoto for one year, after which they will think about what to do next. They learned about the manga museum on the Internet. I’m sure they will come again to read manga and study Japanese here.

Portrait Corner (1F)

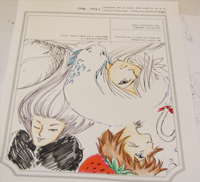

In the Portrait Corner, where visitors have their portraits drawn, I met Catherine and Robert, who were visiting Japan for two weeks from London. They had come to the MM after reading about it in Lonely Planet, which recommended it as one of the best places to visit in Kyoto apart from temples. Robert had become fascinated by Japanese animation after watching Akira (by Katsuhiro Otomo), and he also likes Tekkonkinkreet (by Taiyo Matsumoto) and others. They said that although there are also likeness portraits in London, they tend to be more realistic, whereas the ones at the MM are more uniquely anime- and manga-like. “They’ll make great souvenirs to take home!” they said with satisfied looks when they saw their own portraits, which were finished in about 15 minutes.

In the Portrait Corner, where visitors have their portraits drawn, I met Catherine and Robert, who were visiting Japan for two weeks from London. They had come to the MM after reading about it in Lonely Planet, which recommended it as one of the best places to visit in Kyoto apart from temples. Robert had become fascinated by Japanese animation after watching Akira (by Katsuhiro Otomo), and he also likes Tekkonkinkreet (by Taiyo Matsumoto) and others. They said that although there are also likeness portraits in London, they tend to be more realistic, whereas the ones at the MM are more uniquely anime- and manga-like. “They’ll make great souvenirs to take home!” they said with satisfied looks when they saw their own portraits, which were finished in about 15 minutes.

I asked Takatoshi Okayama (aka Okayama), who had drawn their portraits, what had made him become a portrait artist. A graduate of Kyoto Seika University, he had begun to draw portraits after being introduced to the work by a senior. The joy of portrait drawing, he said, is seeing the delight on the faces of the subjects in front of you. The important thing when drawing is to create a good lasting memory. For example, if it’s spring, Okayama might draw cherry blossoms in the background. If the subject is wearing unique clothing, he might draw the T-shirt pattern or something in detail. If it is a foreigner, he will ask their preference and then draw the portrait in a kimono or ninja costume. In communicating with foreigners, manga is the common language, and it works surprisingly well. “In other situations, I can’t speak a word!” Okayama laughs.

I asked Takatoshi Okayama (aka Okayama), who had drawn their portraits, what had made him become a portrait artist. A graduate of Kyoto Seika University, he had begun to draw portraits after being introduced to the work by a senior. The joy of portrait drawing, he said, is seeing the delight on the faces of the subjects in front of you. The important thing when drawing is to create a good lasting memory. For example, if it’s spring, Okayama might draw cherry blossoms in the background. If the subject is wearing unique clothing, he might draw the T-shirt pattern or something in detail. If it is a foreigner, he will ask their preference and then draw the portrait in a kimono or ninja costume. In communicating with foreigners, manga is the common language, and it works surprisingly well. “In other situations, I can’t speak a word!” Okayama laughs.

The group of people being drawn alongside was the Dromzee family from France. The father, Jean-François, loves Japan and was visiting for the eighteenth time. He was staying for six weeks this time. The mother, Claude, was staying for two weeks, and the daughter and grandchildren for three weeks. The daughter, Anne-Claire, and grandchildren, Capucine and Nino, were having their portraits drawn. Nino liked drawing, and while his mother was having her portrait drawn, he himself got out some paper and pencils and drew the portrait of the artist, which he presented at the end. It was an amusing scene. Even if they could not communicate through language, they could do so through art. The Dromzee family had enjoyed the kamishibai as well.

The group of people being drawn alongside was the Dromzee family from France. The father, Jean-François, loves Japan and was visiting for the eighteenth time. He was staying for six weeks this time. The mother, Claude, was staying for two weeks, and the daughter and grandchildren for three weeks. The daughter, Anne-Claire, and grandchildren, Capucine and Nino, were having their portraits drawn. Nino liked drawing, and while his mother was having her portrait drawn, he himself got out some paper and pencils and drew the portrait of the artist, which he presented at the end. It was an amusing scene. Even if they could not communicate through language, they could do so through art. The Dromzee family had enjoyed the kamishibai as well.

Manga Workshops (1F atrium)

Character Production Workshop (*The workshop schedule changes.)

At the kamishibai and portrait corners, visitors enjoy the performances of the artists and engage in exchange with them. At the manga workshop corner, they actually draw illustrations and manga themselves and can interchange with their companions or other participants.

At the kamishibai and portrait corners, visitors enjoy the performances of the artists and engage in exchange with them. At the manga workshop corner, they actually draw illustrations and manga themselves and can interchange with their companions or other participants.

I spoke with a three-generation family from Osaka that was enjoying manga character production. Ayako Hamada is now a full-time housewife, but previously she worked as a textile designer and was an artist who published picture books. Indeed, the museum staff was impressed by the high quality of the character that she drew in the workshop. Her elder son Taketo, who was absorbed in drawing a character as well, is a third-grade junior high school student who aspires to become a manga artist. Next year he hopes to enter Osaka Prefecture Konan High School of Design and Fine Arts, which his mother also attended.

Ayako’s mother, Kazuko Hashimoto, happily watching the two drawing their manga characters, remarked to me, “It’s all right for a woman, but I was rather worried a bout the future for my grandson. Then I read a pamphlet of Kyoto Seika University t hat I found in this museum titled ‘What can you become after graduating from the Faculty of Humanities?’ and I was relieved to hear that it leads to various occupations.”

Ayako’s mother, Kazuko Hashimoto, happily watching the two drawing their manga characters, remarked to me, “It’s all right for a woman, but I was rather worried a bout the future for my grandson. Then I read a pamphlet of Kyoto Seika University t hat I found in this museum titled ‘What can you become after graduating from the Faculty of Humanities?’ and I was relieved to hear that it leads to various occupations.”

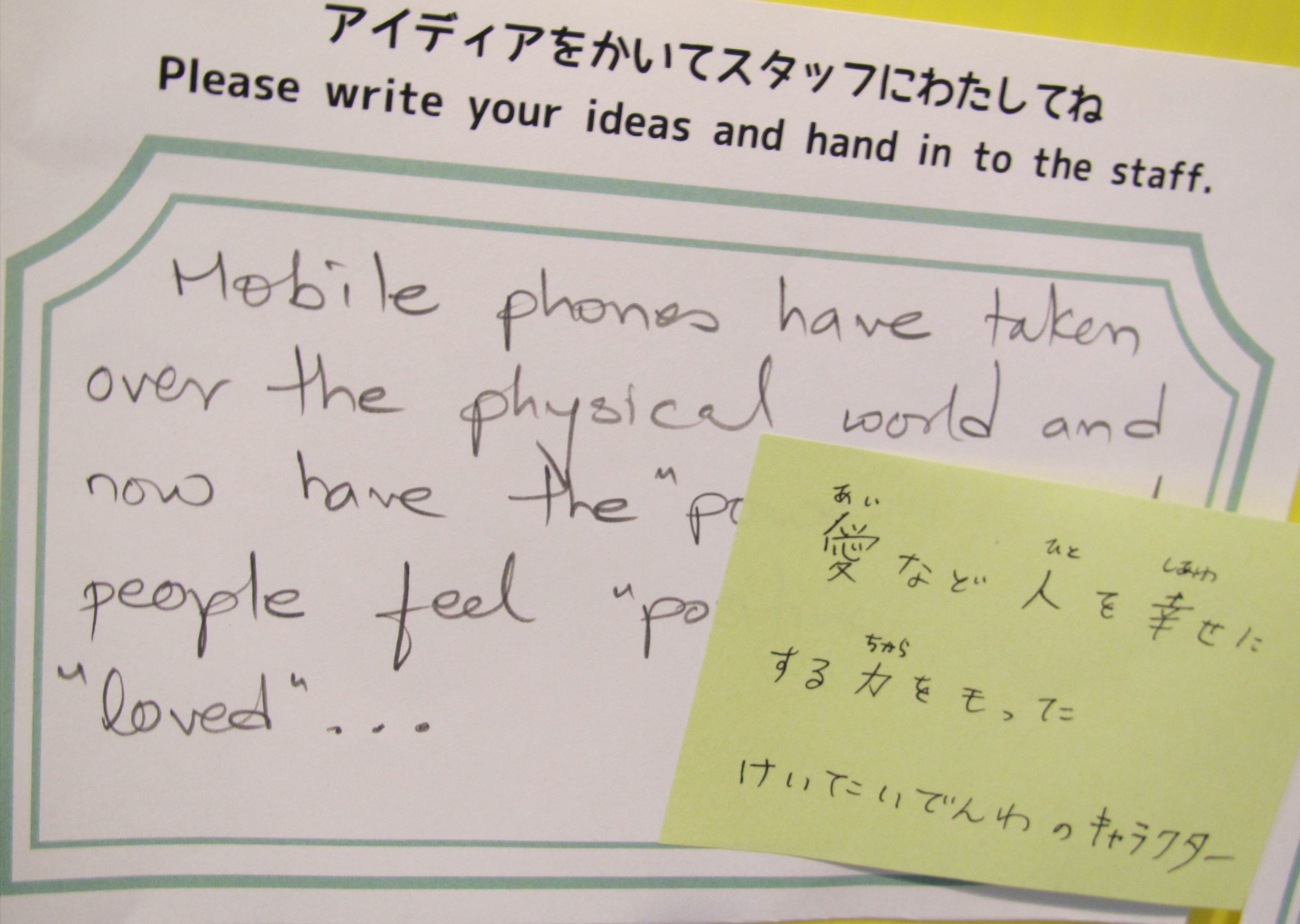

In the space for the character production workshop there is a notice board, so people who cannot draw themselves can think of a character design, stick it on the notice board, and have others finish the drawing for them. When I was checking the ideas of others with the Hamada family, we discovered an interesting idea for a character left by a foreigner. “Maybe I can draw a picture book about this ‘mobile phone character that has the power to make people happy through love,” said Ayako, fired with a creative desire. “I must do my best as a rival so as not to be outdone by my son!”

In the space for the character production workshop there is a notice board, so people who cannot draw themselves can think of a character design, stick it on the notice board, and have others finish the drawing for them. When I was checking the ideas of others with the Hamada family, we discovered an interesting idea for a character left by a foreigner. “Maybe I can draw a picture book about this ‘mobile phone character that has the power to make people happy through love,” said Ayako, fired with a creative desire. “I must do my best as a rival so as not to be outdone by my son!”

The attractions of the workshops are that they enable parents and children to share fun time and, through the ideas on the notice board, to engage in exchange with people who they have never met. The Hamada’s younger son, Akito, who preferred reading manga to drawing them, then returned from the dreamlike world of manga contained in huge bookshelves called the “wall of manga.” When I took a commemorative photo of the family, their impressive smiling faces showed clearly that they had had a good time.

The attractions of the workshops are that they enable parents and children to share fun time and, through the ideas on the notice board, to engage in exchange with people who they have never met. The Hamada’s younger son, Akito, who preferred reading manga to drawing them, then returned from the dreamlike world of manga contained in huge bookshelves called the “wall of manga.” When I took a commemorative photo of the family, their impressive smiling faces showed clearly that they had had a good time.

Special Interview with Researcher

The MM is not only a place where visitors can enjoy manga but also a research institute relating to manga and anime. I spoke with Yoo Sookyung, who is a researcher at Kyoto Seika University’s International Manga Research Center, which is located inside the museum. After graduating from an animation high school in South Korea, Yoo followed an elite manga research course, entering Kyoto Seika University, going on to its graduate school, and then becoming a researcher at the museum. She speaks fluent Japanese and is competent in English and French as well. She answered my questions clearly and unfalteringly.

The MM is not only a place where visitors can enjoy manga but also a research institute relating to manga and anime. I spoke with Yoo Sookyung, who is a researcher at Kyoto Seika University’s International Manga Research Center, which is located inside the museum. After graduating from an animation high school in South Korea, Yoo followed an elite manga research course, entering Kyoto Seika University, going on to its graduate school, and then becoming a researcher at the museum. She speaks fluent Japanese and is competent in English and French as well. She answered my questions clearly and unfalteringly.

Q: What kind of research are you doing?

Q: What kind of research are you doing?

A: I am mainly researching visual expression in girls’ manga—the past and present situation in Japan and the differences between Korean and Japanese manga. For example, there are differences in onomatopoeia depending on the times. In the past a drawing of a character with an angry expression would be accompanied by a word like “Bah!” but nowadays that would seem rather old-fogyish. Now a drawing of an angry character would just be accompanied by the word “Grrr!” written in small letters. The manga marks, or symbols of emotions, have changed as well. For example, the mark as shown on the right above for being angry [“cross-popping veins”] came into use from the 1960s and 70s.

Q: Please tell us about the present state of manga in Japan, including sales of magazines, books, and e-books.

A: A big difference from the past is that magazine sales have declined and run out of steam. In the 1980s boys’ manga magazines would sell five million copies a week, but now the figure is half of that. Book sales have not changed very much, though. And e-books and online manga are not selling as much as expected, which shows the Japanese tendency to favor paper media. Incidentally, in Korea sales of paper media have declined and online manga are doing well.

Regarding readership, the number of small children reading manga has declined. One reason is that children now have a wider choice of games to play, including computer games. Another characteristic is that Shonen Jump is more popular among adult and female readers than before.

Q: What is the difference between Japanese manga and manga of your country, Korea?

Q: What is the difference between Japanese manga and manga of your country, Korea?

A: Even before the lifting of restrictions on Japanese culture in Korea in 1998, pirate and license editions of Japanese manga were being read. I think the foundations of Korean manga were heavily influenced by Japanese manga. You could tell a Japanese manga just by reading it. One major difference is that Japanese manga were magazine-led. If one manga was a hit, artists and editors would rush to incorporate the features in other works, which would create a fad and give a distinct color to each magazine. And a so-called community developed around the magazine. Magazines listened to the opinions and wishes of readers, and sometimes editors would influence artists so as to create fashions and boost circulation. Editors were very powerful. In Korea, on the other hand, manga magazines did not spread until the 1980s. Instead, individual artists would peddle their work to publishers and issue them as books. In Korea the individuality of artists was more central, so there were far fewer fads than there were in Japan.

Q: What is the state of manga and anime in other countries? What manga are popular in what countries and among what kind of readers?

A: The manga boom reached a peak in the West in the 1980s and 90s. Readers at that time are now adults, and they are still reading manga. But the younger generation today is not so interested. One Piece is popular in Japan, but Naruto has more fans in the West. I think the reason is that pirates are not so unusual in the West, but Naruto has an Asian taste and ninja are popular. Doraemon is a favorite, especially in Asia.

Q: Can ordinary visitors ask questions to researchers?

A: The museum curator in the Research Reference Room answers questions. There is no direct contact between researchers and visitors, although if a detailed explanation is necessary, sometimes we reply through the staff in charge of the reference room.

Fluffy Mamyu omelet on rice

Q: Have you had any interesting inquiries from overseas?

A: One foreign manga artist asked why the faces in Japanese manga are all the same. As I said before about magazines, each Japanese manga magazine has its own distinctive color, so perhaps the foreign artist thought so because he was reading manga carried in the same magazine!

Q: As a researcher, how do you recommend visitors to enjoy the museum?

A: For Japanese, manga are a very familiar presence, but conversely that also means there are things that escape their attention. For example, people don’t think about why they understand manga symbols so well even though they never learned them at school, do they? I suggest that they look at the permanent exhibition explaining what manga are and participate in various manga-related events, thereby enjoying manga at the museum from a different perspective than usual. For foreigners, I recommend that they observe Japanese people of whatever age and gender enjoying themselves reading manga at the museum and thereby come to think about the meaning of manga in Japan and the cultural and historical value of manga.

Mamyu,

the manga museum’s

mascot

Kyoto International Manga Museum

Postal Code:604-0846

Karasuma-Oike agaru, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto

TEL:075-254-7414

FAX:075-254-7424

URL:http://www.kyotomm.jp/english/

Open (Museum Hours):10:00-18:00

Closed on every Wednesdays (or, if Wednesday is a national holiday, the following Thursday), During the New Year’s holiday and maintenance periods.

Nearby station:Kyoto city subway Karasuma line or Tozai line,

Karasuma Oike Station, Exit No. 2 (about 2 minute walk)