Echigo-jofu: Traditional Textile of the Snow Country

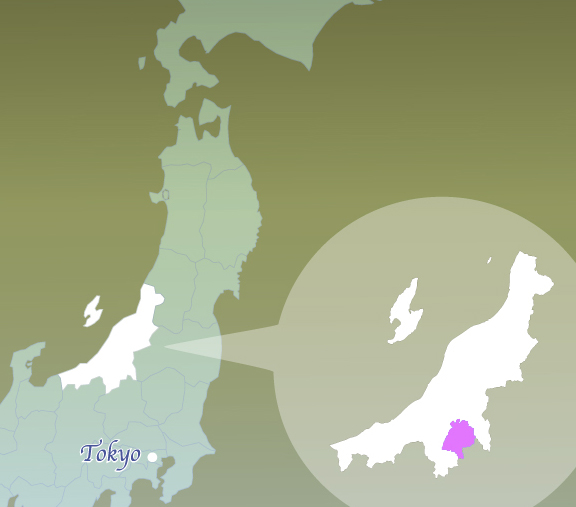

Echigo-jofu is a traditional textile of the Echigo region (present-day Niigata Prefecture), one of the snowiest areas on Japan’s main island of Honshu. The technique for making this famous fabric, which has been handed down over more than 1,200 years, was listed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2009. Mr. Masanori Nagumo is the director of the Shiozawa Tsumugi Pavilion, which carries on traditional crafts, publicizes them, and trains successors. IHCSA Café asked him about this internationally recognized technique, of which Japan is quite rightly very proud.

Echigo-jofu is a traditional textile of the Echigo region (present-day Niigata Prefecture), one of the snowiest areas on Japan’s main island of Honshu. The technique for making this famous fabric, which has been handed down over more than 1,200 years, was listed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2009. Mr. Masanori Nagumo is the director of the Shiozawa Tsumugi Pavilion, which carries on traditional crafts, publicizes them, and trains successors. IHCSA Café asked him about this internationally recognized technique, of which Japan is quite rightly very proud.

Textile Culture Developed in the Snow Country

Among the existing textile fabrics, the Japanese have had a close relationship with hemp since ancient times. Cotton did not become commonplace until the Edo period (1603–1868). There was silk, of course, but that expensive fabric was way out of reach for most ordinary folk. Hemp fabrics spread throughout the country and diversified, but it was in the Shiozawa district of Niigata Prefecture that a traditional and completely hand-woven technique was developed and passed down from generation to generation right up to the present, turning out fabrics of exceptionally high quality.

In the past the Shiozawa district was completely shut off by heavy snow from November until April of the following year, so for farming households making fabrics indoors was an important way of earning some money during the long winter months when they were unable to engage in outdoor farm work. They went about the task not as a hobby or recreation but as a means of scraping a living. During the period when work on the land was out of the question, the women turned to fabric making. Daughters saw their mothers and grandmothers working at the loom and assumed it was their calling as well.

From Hemp to Yarn

Echigo-jofu fabric is made from the ramie plant, which is a kind of hemp. Hemp other than ramie is strong and suitable for rope and bags, but ramie has a lightness that makes it ideal for clothing.

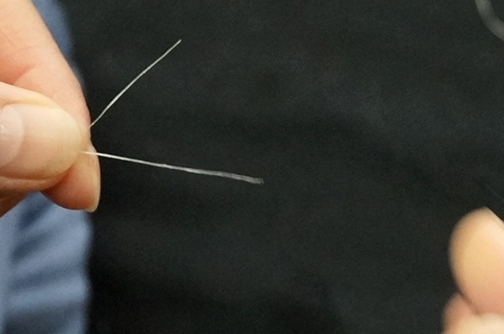

First of all, the bark is peeled off the plant stem and placed on a board to be scraped with a metal instrument, which separates the soft tissue and hard fiber (the stringy part). Then the fiber is split by fingernail into strands thinner than hair, which are joined together to form long yarn. In the case of Echigo-jofu, the thickness of the fiber when split becomes the thickness of the yarn; there is no intertwining. The thinness of the split fiber influences the price of the fabric. The finished yarn is then gathered together and placed on top of the snow for sunlight bleaching. This results in a high degree of whiteness that cannot be achieved in other producing regions.

The soft tissue is removed, and

then the fiber is split by fingernail

into strands thinner than hair.

Two strands of fiber are joined to form

long yarn. This thin yarn is then used

to weave the fabric.

Dyeing the Yarn to Form a Pattern

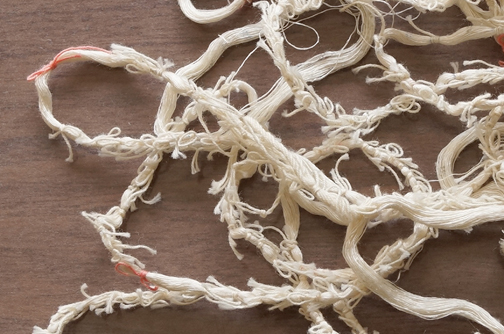

The colorful patterns on the finished fabrics are formed by using yarn that has been dyed beforehand in accordance with a diagram. These finished patterns are called kasuri (literally, blurred patterns). The outstanding feature of Echigo-jofu is the resist-dyeing technique of kubiri (tying or binding). In this technique, before the dyeing, yarn for the part to be kept white in accordance with the sketched pattern are marked and tightly bound together with separate thread to prevent the dye from penetrating. All of the yarn for the fabric is then soaked in dye. When the binding thread is removed afterward, this part remains white, enabling the pattern to be woven into the fabric.

A bundle of yarn before

dyeing: The fluffy paxrt is

the section bound tightly in

white cotton thread to

prevent it from being dyed.

The binding is removed

after dyeing, and the

unbundled yarn is used as

weft in weaving the fabric.

The bound weft yarn

remains undyed in

accordance with the

desired pattern. Each yarn

is then woven to create the

pattern.

In the case of fabric with a white background, a spatula is used to dye only the part to be colored. If the whole background is to be dyed, the parts already colored using a spatula are bound with thread to prevent the next dye from penetrating, and then the whole bundle of yarn is dyed. If many colors are to be used, each color has to be repeatedly imprinted by hand using a spatula, and these parts have to be bound tightly to preserve their colors before being soaked in the dye. It is a meticulous and painstaking process.

If a multicolored pattern is to be created on a

fabric with a white background, the weaving

thread is colored beforehand using a spatula

in accordance with the desired pattern.

If another color is to be applied, the part that

has been colored using a spatula is bound

tightly with thread and then the whole yarn is

put into the dye. It is a meticulous process.

The length of the fabric to be woven at a width of 38 centimeters is 13 meters. There are nine weft threads in each space of 3.8 millimeters. The finished fabric will be appraised by the fineness of the pattern, the number of colors in the pattern, and the size of the pattern, and its price will reflect these factors.

Elaborate Work on the Loom

Ground loom

Keeping the yarn moist with wet cotton

Echigo-jofu fabric is not something that can be weaved like clockwork. The pattern is crafted in accordance with the diagram by carefully making adjustments every time a weft thread is passed through so that the dyed parts correspond precisely to the sketch. Working every day from early morning until late at night, it takes from three to six months to produce one roll of fabric (enough for one kimono). In other words, it takes a household all winter to make one roll of fabric.

Midwinter is the best time for weaving Echigo-jofu fabric. Every year, even today, this district is buried in a couple of meters of snow; in the past it used to snow even more heavily. As a result of the constantly falling snow, the ground floors of houses were cold and damp, creating just the right conditions for weaving with ramie thread, which snaps easily when dry. During the months when outdoor work was impossible, the climate of this district was ideal for indoor weaving.

Removing Starch with Soles of Feet

After the weaving is over, the starch contained in the yarn has to be removed. Starch is added to the yarn in order to make it smoother and facilitate the work. After rubbing the fabric in hot water, it is soaked in cold water and trampled underfoot. This foot-trampling process also has the effect of sealing the warp and weft meshes and stabilizing the fabric. It requires skill to make sure that the whole fabric is foot-massaged uniformly. The subtle sensation conveyed by the feet also gives an inkling of how the finished product is going to turn out.

After the weaving is over, the starch contained in the yarn has to be removed. Starch is added to the yarn in order to make it smoother and facilitate the work. After rubbing the fabric in hot water, it is soaked in cold water and trampled underfoot. This foot-trampling process also has the effect of sealing the warp and weft meshes and stabilizing the fabric. It requires skill to make sure that the whole fabric is foot-massaged uniformly. The subtle sensation conveyed by the feet also gives an inkling of how the finished product is going to turn out.

Sunlight Bleaching on the Snow

The final process involves bleaching by spreading the fabric over the snow. The ozone released when ultraviolet rays hit the surface of the snow has the effect of bleaching the vegetable fiber colors. Whiter parts become whiter, and colored parts become even more vivid. In this district the fields are still covered in snow at the beginning of spring. The fabrics weaved over winter are spread out on top of this snow and left in the sunlight for 7 to 10 days.

The final process involves bleaching by spreading the fabric over the snow. The ozone released when ultraviolet rays hit the surface of the snow has the effect of bleaching the vegetable fiber colors. Whiter parts become whiter, and colored parts become even more vivid. In this district the fields are still covered in snow at the beginning of spring. The fabrics weaved over winter are spread out on top of this snow and left in the sunlight for 7 to 10 days.

Master Craft Deserves Preservation

High-class Echigo-jofu fabrics woven in this way breathe well and have a comfortable lightness, which makes them ideal for use in summer kimonos. The smooth hemp cloth, which is so thin as to be almost transparent, gives a pleasant sense of coolness and has a very soft texture. Not surprisingly, these fabrics made so meticulously in the snow country were highly appraised and offered as gifts to people in powerful positions throughout the country, including military generals and feudal lords.

High-class Echigo-jofu fabrics woven in this way breathe well and have a comfortable lightness, which makes them ideal for use in summer kimonos. The smooth hemp cloth, which is so thin as to be almost transparent, gives a pleasant sense of coolness and has a very soft texture. Not surprisingly, these fabrics made so meticulously in the snow country were highly appraised and offered as gifts to people in powerful positions throughout the country, including military generals and feudal lords.

Echigo-jofu fabrics have reached their present high level by bringing together various techniques performed by hand, such as the yarn-making process, resist-dyeing to create patterns, weaving by ground loom, trampling by foot to remove starch, and bleaching in the snow. Before the Edo period each farming household used to carry out every process, but later a division of labor began for the cultivation of ramie, dyeing, and so on, resulting in even higher-quality fabrics.

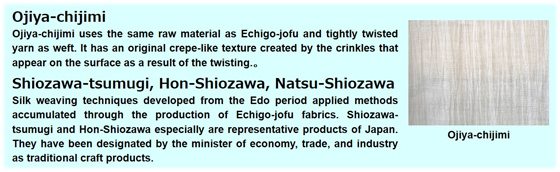

In 1955 the Echigo-jofu technique, consisting of five traditional processes, was designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan. “These techniques,” it was stated, “display the special cultural characteristics of the snow country region and are important for their use of genuinely traditional methods for everything from the raw materials to the processing technique.” Half a century later, this technique, which has remained unchanged since ancient times, received international recognition and was registered, along with Ojiya-chijimi, which is produced in the neighboring Ojiya district, on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Tradition and Innovation

Shiozawa-tsumugi, Hon-Shiozawa, and Natsu-Shiozawa, which are silk textiles made in Shiozawa, are also highly appraised, and in recent years fabrics blending hemp, silk, and cotton have appeared as well. Shiozawa Tsumugi Pavilion Director Nagumo remarked, “Without reforms of some kind, tradition is going to die out. Unless some changes are made, it is just going to become something old-fashioned and disappear. That’s true for everything, not only textiles. Reforms are essential in order to safeguard the tradition. However good something might be, it’s pointless unless there is someone to wear it or use it. And without reforms, young people won’t become interested either.” His words point to the difficulty of maintaining traditions and the importance of challenging new things while protecting those traditions.

Shiozawa Tsumugi Pavilion Director Nagumo: “Ask me anything!”

Editorial and photo cooperation:

Shiozawa Tsumugi Pavilion

1227-14, Shiozawa, Minamiuonuma-city,

Niigata, 949-6408

TEL.025-782-4888 FAX.025-782-1148

http://tsumugi-kan.jp/ (Japanese only)

Photo cooperation:

Shiozawa textile industry cooperative