Osaka—A Gastronomic Wonderland

Osaka is said to be a culinary capital. Reading Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, written by Shizuo Tsuji, founder of the Tsuji Culinary Institute, the British food journalist Michael Booth was amazed to learn that concepts currently in vogue in contemporary Western-style cooking, such as simplicity, letting the ingredients speak for themselves, and seasonal food, had been talked about so vividly in a book introducing Japanese cuisine written back in 1980. As a result of reading Tsuji’s book, Booth became profoundly interested in Japanese food and decided to make a three-month “foodie road trip” across Japan together with his family. He describes his experiences on that tour in a book titled Sushi and Beyond: What the Japanese Know about Cooking. In that book, Booth writes about food in Osaka. He notes that the respected French restaurant critic Francois Simon told him that Osaka was “his favorite food city in the world” and adds that “I have seen it [Osaka] name-checked in several interviews with top European and US chefs as a place they visit for inspiration.” The book goes on to describe how Booth himself relished his visit to the city, going not only to high-class restaurants but also okonomiyaki, kushikatsu, and other eateries frequented by ordinary folk. After reading Booth’s book, I smacked my lips and knew there was only one place to go—Osaka!

The origin of okonomiyaki apparently goes way back to the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1600), when the tea master Sen no Rikyu served similar confectionery at tea ceremonies. Later, a style of cooking developed in which something would be wrapped in a crust baked by combining flour and water and eaten as a substitute for a main meal. This style took various forms in the Edo, Meiji, and Taisho periods, but it was not until after World War II, in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, that the contemporary style of okonomiyaki appeared, with egg, cabbage, and other ingredients mixed into the batter. Osaka-style okonomiyaki is representative of the city’s cheap yet delicious B-grade gourmet food. I visited a couple of okonomiyaki restaurants to learn about the secrets of its popularity.

Kiji (Main Restaurant): 1F/2F Shin-Umeda Shokudo-gai, 9-20 Kakuda-cho, Kita-ku

The Shin-Umeda Shokudo-gai food mall, situated above Umeda Station on the Midosuji subway line and below the elevated JR Tokaido Line, was opened in 1950. Perhaps because some restaurants date from that time, the mall has a rather nostalgic Showa-like atmosphere. One of the popular eateries in this mall is the okonomiyaki restaurant Kiji, which is especially famous for the long queue of customers waiting outside.

The Shin-Umeda Shokudo-gai food mall, situated above Umeda Station on the Midosuji subway line and below the elevated JR Tokaido Line, was opened in 1950. Perhaps because some restaurants date from that time, the mall has a rather nostalgic Showa-like atmosphere. One of the popular eateries in this mall is the okonomiyaki restaurant Kiji, which is especially famous for the long queue of customers waiting outside.

Kiji was just a bar when it opened in 1954, so it is not very spacious. Actually, media coverage is not very welcome here. Ippei Kiji, the manager and one of the original founder’s family members, explains with a bashful smile, “We are grateful for being introduced. But the place is so small, if lots of people came, we just couldn’t cope.”

Kiji was just a bar when it opened in 1954, so it is not very spacious. Actually, media coverage is not very welcome here. Ippei Kiji, the manager and one of the original founder’s family members, explains with a bashful smile, “We are grateful for being introduced. But the place is so small, if lots of people came, we just couldn’t cope.”

I ordered the modan-yaki and gyusuji okonomiyaki, which receive very good reviews on Internet sites. Modan-yaki, which is batter added to fried noodles, seemed somewhat thinner than Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki. When I asked, I was told the characteristic of this dish is that the batter contains only eggs and no flour. The helping would not be too much for one woman, and it might go well with a bowl of rice too.

The gyusuji (beef tendon) okonomiyaki, meanwhile, was full and voluminous. Yam and baking powder are mixed into the batter in superb amounts. Watching the cooking process, I saw how plenty of vegetables are mixed into the batter, on top of which is placed one perilla leaf, on top of which are scattered lots of green onions and finally beef tendon.

One modan-yaki and one gyusuji okonomiyaki would be just the right amount when shared between two people. The tasty sauce contains secret spices. If it hadn’t been lunchtime, a beer would have gone down well with it too.

Fukutaro (Sennichi-mae Main Restaurant): 2-3-17 Sennichi-mae, Chuo-ku

One more place recommended by an Osaka resident and rated highly on the Internet was the okonomiyaki and teppanyaki restaurant Fukutaro. According to Fukutaro’s website, the attractions of this restaurant are its excellent ingredients (prime Kobe beef, top-quality Kagoshima pork, and seafood from the Osaka Central Wholesale Market) and the skills of its veteran chef.

One more place recommended by an Osaka resident and rated highly on the Internet was the okonomiyaki and teppanyaki restaurant Fukutaro. According to Fukutaro’s website, the attractions of this restaurant are its excellent ingredients (prime Kobe beef, top-quality Kagoshima pork, and seafood from the Osaka Central Wholesale Market) and the skills of its veteran chef.

Yasuo Nakanishi, who appears on a sticker wielding teppanyaki spatulas, is the president of Fukutaro and also manager of the Sennichi-mae main restaurant. I wanted to meet this veteran chef and observe his deft handling of the spatula for myself, but unfortunately the day of my visit was his day off.

Yasuo Nakanishi, who appears on a sticker wielding teppanyaki spatulas, is the president of Fukutaro and also manager of the Sennichi-mae main restaurant. I wanted to meet this veteran chef and observe his deft handling of the spatula for myself, but unfortunately the day of my visit was his day off.

Opened in 1996, Fukutaro is certainly not an old restaurant, but nevertheless it has become very popular. I telephoned Mr. Nakanishi and asked about the secrets behind this popularity. First of all, he replied, Fukutaro uses kombu (seaweed) stock in making the batter, and the plain flour used is especially fine. Unlike Kansai-style okonomiyaki, he explained, they do not mix cabbage or other ingredients into the batter. Instead, the batter is added several times as the ingredients are being cooked, which is why it is said to be rather similar to Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki. Also, the iron plate used for cooking is 30 mm thick, so the pancake is heated over a strong fire. As a result, although the inside is soft and juicy, the surface is fragrant and crisply cooked.

On my visit, I tried the pork and green onion okonomiyaki, beef tendon and green onion okonomiyaki, and “Special Yakisoba Part 2.” Completely overturning my existing idea of okonomiyaki, the sauce used for the green onion okonomiyaki was based on soy sauce.

Fukutaro attracts many foreign customers, so it has an English menu. The comments on Trip Advisor, a website of worldwide travel reviews, attest to the restaurant’s popularity among foreigners.

Takoyaki are made by mixing chopped octopus in a batter made from flour, like okonomiyaki, and cooking the mixture in semispherical hollows with a diameter of 3–5 cm set in an iron plate to produce balls. Takoyaki are said to have been started by Tomekichi Endo, the first-generation owner of the Aizuya restaurant in Nishinari-ku, Osaka, in 1935.

Yamachan (Main Shop): 1-2-34 Abenosuji, Abeno-ku

In March 2014 Abeno Harukas, the tallest building in Japan (rising 300 meters high), opened at Kintetsu Osaka Abenobashi Station (adjacent to the JR or Midosuji subway Tennoji Station). Just a stone’s throw from Abeno Harukas, the most talked-about building in Osaka at the moment, is the main shop of Yamachan, a popular takoyaki eatery. The characteristics of Yamachan’s takoyaki are said to

In March 2014 Abeno Harukas, the tallest building in Japan (rising 300 meters high), opened at Kintetsu Osaka Abenobashi Station (adjacent to the JR or Midosuji subway Tennoji Station). Just a stone’s throw from Abeno Harukas, the most talked-about building in Osaka at the moment, is the main shop of Yamachan, a popular takoyaki eatery. The characteristics of Yamachan’s takoyaki are said to be their crispness and juiciness. I asked Shingo Koshitani, the manager of Yamachan’s main shop, about the secret.

be their crispness and juiciness. I asked Shingo Koshitani, the manager of Yamachan’s main shop, about the secret.

One vital concern, he told me, is the stock used when making the batter. Starting at 4 in the morning, the stock is made by adding vegetables, such as onions, cabbage, carrots, celery, and green onions, and fruit like pineapples, bananas, and apples to a chicken and dried bonito broth and boiling the mixture for four hours before finally adding kombu stock. The batter made by adding flour to this stock is more runny (more watery) than ordinary batter.

Another key feature is the specially ordered thick iron plate, which enables the runny batter to be cooked at a high temperature for a long time. The hollows in the iron plate are a wide 4.5 cm in diameter, so the mixture is cooked for nearly 15 minutes rather than the usual four to five minutes. As a result, he said, the surface is crisp and the inside is juicy.

Another key feature is the specially ordered thick iron plate, which enables the runny batter to be cooked at a high temperature for a long time. The hollows in the iron plate are a wide 4.5 cm in diameter, so the mixture is cooked for nearly 15 minutes rather than the usual four to five minutes. As a result, he said, the surface is crisp and the inside is juicy.

Since the stock is so flavorsome, customers are  recommended to eat the takoyaki without adding anything. I sampled takoyaki without sauce, as well as takoyaki with a topping of mayo + soy sauce (“Young B”) and sesame oil + salt. The sesame oil was fragrant and tasty, but personally I really liked the “Young B,” a superb combination of soy sauce and mayonnaise. According to Mr. Koshitani, regular customers have their favorites and always order the same thing.

recommended to eat the takoyaki without adding anything. I sampled takoyaki without sauce, as well as takoyaki with a topping of mayo + soy sauce (“Young B”) and sesame oil + salt. The sesame oil was fragrant and tasty, but personally I really liked the “Young B,” a superb combination of soy sauce and mayonnaise. According to Mr. Koshitani, regular customers have their favorites and always order the same thing.

Sennichi-mae, which is located at the southeastern end of the Dotombori area, is an entertainment district with many theaters, cinemas, and other attractions. Although some old cabarets and other establishments still line the backstreets, many closed down after the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s. Since around 2010, however, the district’s old-time atmosphere and cheap rents have become an attraction, and many new eating and drinking establishments are appearing one after the other in what has become known as Uranamba (“back side of Namba”).

Ushitora: 15-19 Sennichi-mae, Namba, Chuo-ku

This standing bar, also recommended to me by a local resident, is highly rated on restaurant review sites. The top page of Ushitora’s section on a review site, however, carries a note of caution: “Ushitora is a standing bar and not a place for long stays. It is not appropriate for merrymaking like an izakaya. Please come alone or in pairs.” As there were three of us, it was with a little trepidation that we headed for the bar.

This standing bar, also recommended to me by a local resident, is highly rated on restaurant review sites. The top page of Ushitora’s section on a review site, however, carries a note of caution: “Ushitora is a standing bar and not a place for long stays. It is not appropriate for merrymaking like an izakaya. Please come alone or in pairs.” As there were three of us, it was with a little trepidation that we headed for the bar.

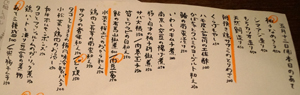

Ushitora is located on the first floor of a small building on a side street near Namba Station, the terminus of the Nankai Main Line. The wide, open entrance had a hanging curtain (noren) and was covered by a transparent vinyl sheet. Although it was a rainy Monday, the bar, which has a capacity of 22 customers, was almost full. The menu offered an impressive range of Japanese sake. I ordered Aizu sake, which is one of my favorites. There was a wide range of side dishes to go with the sake too, and they were incredibly cheap—¥500 for an assortment of three hors d’oeuvres and ¥180 for ginger tempura. And not only that, they were delicious as well. I was very satisfied indeed. Incidentally, the three of us had four glasses of sake and three hors d’oeuvres, and the total bill came to about ¥3,200. Ushitora really is the ultimate standing bar where you can find satisfaction for just ¥1,000 per person.

Ushitora is located on the first floor of a small building on a side street near Namba Station, the terminus of the Nankai Main Line. The wide, open entrance had a hanging curtain (noren) and was covered by a transparent vinyl sheet. Although it was a rainy Monday, the bar, which has a capacity of 22 customers, was almost full. The menu offered an impressive range of Japanese sake. I ordered Aizu sake, which is one of my favorites. There was a wide range of side dishes to go with the sake too, and they were incredibly cheap—¥500 for an assortment of three hors d’oeuvres and ¥180 for ginger tempura. And not only that, they were delicious as well. I was very satisfied indeed. Incidentally, the three of us had four glasses of sake and three hors d’oeuvres, and the total bill came to about ¥3,200. Ushitora really is the ultimate standing bar where you can find satisfaction for just ¥1,000 per person.

A glance at the long counter showed that there were quite a few couples. The manager, Mako Yoshida, told me that some women come here alone. Naked light bulbs shine over the wooden counter, and the tables consist of no more than boards placed over beer bottle cases, but nonetheless, for a standing bar, Ushitora has a nice, cozy atmosphere.

When I asked about the cautionary note on the review site, Ms. Yoshida explained, “This is not a place for rowdy drinking. We want it to be a quiet place where people can soothe themselves after a hard day. So if people are being a nuisance to others, we ask them to leave. We don’t accept groups of more than five people.”

Eighty-five years have passed since Yoshie Momono first served kushikatsu at Daruma, in a corner of the Osaka Shinsekai district, back in 1929. As suggested by the symbolic name of Shinsekai (“New World”), this district was an imitation of Paris and New York at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was a huge entertainment center with, among other things, a tower, amusement park, theaters, cinemas, and a zoo. Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, though, it suffered a decline toward the end of the century. Public order deteriorated, and it seemed as if the district had fallen behind the times. Recently, however, the nostalgic Showa atmosphere of the area has become a tourist resource and, centering on the Tsutenkaku tower, restaurants specializing in kushikatsu, which were invented here, and other eateries have become popular among sightseers.

Daruma (Tsutenkaku Restaurant): 1-6-8 Ebisu-higashi, Naniwa-ku

Michael Booth mentions the Daruma kushikatsu restaurant in his book. Booth writes of kushikatsu: “This is another of the great Osakan fast foods, and deserves to be right up there with tempura and yakitori … as a globally known Japanese style of cooking.” Booth also quotes the chef as having said that Ferran Adria had eaten here recently. (Adria was the head chef of El Bulli in Spain, a restaurant at which it was notoriously difficult to make a booking, and is considered to be one of the finest chefs in the world.) In April of this year Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also visited Daruma, where he ate the Tsutenkaku kushikatsu set, but Adria’s visit was probably the bigger news.

Michael Booth mentions the Daruma kushikatsu restaurant in his book. Booth writes of kushikatsu: “This is another of the great Osakan fast foods, and deserves to be right up there with tempura and yakitori … as a globally known Japanese style of cooking.” Booth also quotes the chef as having said that Ferran Adria had eaten here recently. (Adria was the head chef of El Bulli in Spain, a restaurant at which it was notoriously difficult to make a booking, and is considered to be one of the finest chefs in the world.) In April of this year Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also visited Daruma, where he ate the Tsutenkaku kushikatsu set, but Adria’s visit was probably the bigger news.

There is always a queue outside Daruma, so the manager of Daruma’s Tsutenkaku restaurant, Kiyoaki Kawabata, asked me to come along for the interview before opening time. As requested, I turned up an hour before the restaurant opened its doors. When I looked into the kitchen of the still shuttered restaurant, the first thing I noticed was the orderly assembly of ingredients. They looked as if they would be tasty even if eaten without being cooked. Regarding the batter, Booth explains in his book that it is made with pureed yams, flour, water, and a unique blend of spices. Mr. Kawabata said with a laugh, “The sauce and batter have been a company secret since 1929!” Regarding the oil, he told me that since they use special oil using beef suet, it is not so greasy.

There is always a queue outside Daruma, so the manager of Daruma’s Tsutenkaku restaurant, Kiyoaki Kawabata, asked me to come along for the interview before opening time. As requested, I turned up an hour before the restaurant opened its doors. When I looked into the kitchen of the still shuttered restaurant, the first thing I noticed was the orderly assembly of ingredients. They looked as if they would be tasty even if eaten without being cooked. Regarding the batter, Booth explains in his book that it is made with pureed yams, flour, water, and a unique blend of spices. Mr. Kawabata said with a laugh, “The sauce and batter have been a company secret since 1929!” Regarding the oil, he told me that since they use special oil using beef suet, it is not so greasy.

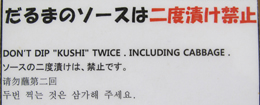

This restaurant was the birthplace of not only kushikatsu but also the “no double dipping” rule. Next to the communal sauce pots on the counter there are warnings to this effect written in four languages: Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean.

After finishing taking photos, I ate my kushikatsu. Although it had cooled down a bit, it still had that crispy and chewy feel. Most delicious!

My eating tour, arranged with the cooperation of the Osaka Government Tourism Bureau, took me in a day and a half to two okonomiyaki restaurants, one takoyaki shop, two kushikatsu restaurants, and two standing bars. (Doesn’t tally with the above? That’s right, besides the research for this article, I added one kushikatsu restaurant and one standing bar to my itinerary myself!) I was exhausted from eating. But while half of me was crying out that I had had enough doughy food for quite some time, the other half was already thinking about where to go next time. I thoroughly recommend readers to visit Osaka and savor its culinary fare.

Cooperation: Osaka Government Tourism Bureau (Osaka Convention and Tourism Bureau)

Reference: Sushi and Beyond: What the Japanese Know about Cooking, Michael Booth, Vintage, 2010

Websites of Visited Restaurants and Review Sites

Kiji (okonomiyaki)

Tabelog (Japanese): http://tabelog.com/osaka/A2701/A270101/27000297/

Trip Advisor (English): http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Restaurant_Review-g298566-d1700918-Reviews-Kiji-Osaka_Osaka_Prefecture_Kinki.html

Fukutaro (okonomiyaki)

Website (Japanese): http://2951.jp/

Trip Advisor (English):http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Restaurant_Review-g298566-d3610195-Reviews-Fukutaro-Osaka_Osaka_Prefecture_Kinki.html

Yamachan (takoyaki)

Website (English): http://takoyaki-yamachan.net/shop/honten/?lang=en

Tabelog(Japanese): http://tabelog.com/osaka/A2702/A270203/27002750/

Ushitora (standing bar)

Tabelog (Japanese): http://tabelog.com/osaka/A2702/A270202/27017138/

Trip Advisor (English): http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Restaurant_Review-g298566-d6591796-Reviews-Ushitora-Osaka_Osaka_Prefecture_Kinki.html

Daruma (kushikatsu)

Website (Japanese): http://www.kushikatu-daruma.com/tenpo_tsutenkaku.html

Trip Advisor (English): http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/ShowUserReviews-g298566-d1681413-r178704787-Gansokushikatsu_Daruma_Tsutenkaku-Osaka_Osaka_Prefecture_Kinki.html

- Category

- Cusine、Food、Local specialties、News、Restaurants、Travel