The Nature and Blessings of Amami-Oshima Part 2: Brown-Sugar Shochu and Amami Cuisine

The Nature and Blessings of Amami-Oshima

Part 2: Brown-Sugar Shochu and Amami Cuisine

When you travel somewhere for the first time, you want to taste that place’s cuisine. Personally, I want to try the local sake too. So I asked an acquaintance of mine, Mr. Shinichiro Sato, who works as a guide for the Amanico Guide Service on Amami-Oshima, to plan a one-day tour to explore the local cuisine of Amami. Let me introduce, with photos, my day there in which I encountered the traditional shimameshi food, the brown-sugar shochu (distilled liquor) that can only be made in the Amami region, and the local fish that go so well with this drink.

Tasting the blessings of nature (Shimameshiya Kano) For lunch I had traditional local food at the Shimameshiya Kano restaurant, which was recommended by Mr. Sato. Actually, the meat used in the local rice food differs in the northern and southern parts of the island. While the south, influenced by Okinawa, uses pork, the north uses chicken, which, it is said, was served to officials of the Satsuma clan in the Edo period (1603–1868). In the city of Amami in the middle of Amami-Oshima you can see many restaurant signboards advertising keihan (chicken rice), and it is this chicken rice that is sold at souvenir shops as well. Shimameshiya Kano is located in the town of Setouchi-cho in the southern part of the island, so the main lunch set there is pork rice (which at the Kano restaurant is called tonhan).

For lunch I had traditional local food at the Shimameshiya Kano restaurant, which was recommended by Mr. Sato. Actually, the meat used in the local rice food differs in the northern and southern parts of the island. While the south, influenced by Okinawa, uses pork, the north uses chicken, which, it is said, was served to officials of the Satsuma clan in the Edo period (1603–1868). In the city of Amami in the middle of Amami-Oshima you can see many restaurant signboards advertising keihan (chicken rice), and it is this chicken rice that is sold at souvenir shops as well. Shimameshiya Kano is located in the town of Setouchi-cho in the southern part of the island, so the main lunch set there is pork rice (which at the Kano restaurant is called tonhan).

Mr. Tatsuro Kano, the owner of Shimameshiya Kano, calls himself a “farmer who makes naturally cultivated brown sugar.” He grows sugarcane, vegetables, citrus fruits, and other crops without using any agrochemicals or administering fertilizer. Moreover, his wife, Junko, then prepares dishes that make one sense Amami’s nature using the delicious brown sugar and other products grown by her husband as ingredients.

Tatsuro and Junko Kano

Look at the photos of my lunch set. The white food on the oblong plate at the front is desalted pork. The tonhan dish uses salted pork, which was a preserved food in the past when there were no refrigerators. Since this salted pork is awfully salty, it is soaked in water for several days to remove the salty taste. Beside the pork are shredded egg from local chickens and shiitake. The photo on the upper left shows local purple yam fried deeply to give it a chewy texture, and to the right of that are simmered vegetables grown, like the sweet potatoes, by her husband.

The three small dishes on the right are condiments. The pinky condiment is local ginger, the orange one with a green line is thin-sliced pickled papaya, and the green one is finely chopped lemon skin. Everything here has been cooked by Junko using ingredients grown by Tatsuro.

The three small dishes on the right are condiments. The pinky condiment is local ginger, the orange one with a green line is thin-sliced pickled papaya, and the green one is finely chopped lemon skin. Everything here has been cooked by Junko using ingredients grown by Tatsuro.

The dish at the very top is a bowl of rice cooked in a broth, which is eaten with toppings of accompanying dishes, condiments, and so on. First you taste all the accompanying dishes, then you eat them on rice, and finally you pour on the broth in the small pot shown partially in the far right of the photo and eat it just like ochazuke (rice with tea poured on it). Everything has a gentle flavor, not only the naturally grown vegetables, of course, but also the desalted pork and the broth poured over the pork rice. The flavor of the broth is something like adding pork extract to the clear soup used for ozoni (traditional Japanese rice cake soup eaten on New Year’s day) in Tokyo. It was, I thought, the flavor of Amami-Oshima. I had never tasted anything like it before.

Roselle fruit

Roselle tea made by drying the calyxes and husks of the roselle fruit

The island’s blessings were fully apparent not only in the cuisine but in the beverages too. The self-service drink bar offered several kinds of herb tea, including lemongrass, shell ginger, and roselle. I had a hot roselle tea. When I poured in some hot water, the liquid turned pink and then, after a while, a darker pink like a hibiscus flower. On a rainy November day, which was cool for Amami- Oshima, and which the Kano couple said was “chilly,” it was a heartwarming drink for both body and mind.

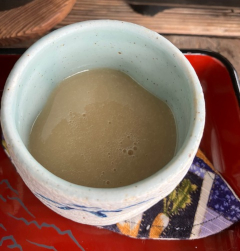

There was another unfamiliar drink, called miki, placed alongside the bowl of rice. Although the ingredients and production methods vary in the bow-shaped string of islands including Okinawa, Miyako, and the Yaeyama isles, this is a fermented drink offered to the gods at Shinto ceremonies and festivals. The name is said to derive from the Japanese word for sacred wine (miki). The drink that I had was made from sweet potato and rice with brown sugar added. Despite the fact that the drink is vegetarian, it includes, like yoghurt, much lactic acid bacteria. So even people who have dairy product allergies, or people who want to avoid animal-derived products, can drink it as a lactic-acid beverage. It contains no alcohol.

There was another unfamiliar drink, called miki, placed alongside the bowl of rice. Although the ingredients and production methods vary in the bow-shaped string of islands including Okinawa, Miyako, and the Yaeyama isles, this is a fermented drink offered to the gods at Shinto ceremonies and festivals. The name is said to derive from the Japanese word for sacred wine (miki). The drink that I had was made from sweet potato and rice with brown sugar added. Despite the fact that the drink is vegetarian, it includes, like yoghurt, much lactic acid bacteria. So even people who have dairy product allergies, or people who want to avoid animal-derived products, can drink it as a lactic-acid beverage. It contains no alcohol.

Sugarcane field

Hand-picked sugarcane

After my meal, Mr. Kano showed me the sugarcane field. Mr. Kano said he takes great care not to use fertilizer in making the soil; to return weeds, sugarcane leaves, and so on to the field; to hand-pick the sugarcane one by one; to make the brown sugar by a traditional production method using firewood; and, rather than completing the entire harvesting in the winter months from December to April, harvesting and producing the brown sugar throughout the year.

Brown sugar made by Mr. Kano

Brown-sugar shochu (Nishihira Honke) On the afternoon of that day I visited the Nishihira Honke distillery, for which Mr. Sato works as a brown-sugar shochu ambassador. Since November is not the time of year for making shochu, I was not able to actually see the process. But while looking at the equipment standing quietly inside the postseason distillery, I learned about the process.

On the afternoon of that day I visited the Nishihira Honke distillery, for which Mr. Sato works as a brown-sugar shochu ambassador. Since November is not the time of year for making shochu, I was not able to actually see the process. But while looking at the equipment standing quietly inside the postseason distillery, I learned about the process.

(The photos were taken during the shochu-brewing season; courtesy of Nishihira Honke.)

The first stage of the process involves applying kojikin mold to rice and, after leaving it for about two days, adding yeast and water to make the primary mash. Having visited Japanese sake breweries several times, I was surprised that the process is the same as that for sake. In alcoholic drinks, yeast converts the sugar into alcohol. So why, I thought, is the brown sugar not just turned into alcohol at that stage? Mr. Tomofumi Nakamura of the Nishihira Honke’s Production Section replied to my simple query with a smile, saying “Then that would be rum, wouldn’t it?”

The first stage of the process involves applying kojikin mold to rice and, after leaving it for about two days, adding yeast and water to make the primary mash. Having visited Japanese sake breweries several times, I was surprised that the process is the same as that for sake. In alcoholic drinks, yeast converts the sugar into alcohol. So why, I thought, is the brown sugar not just turned into alcohol at that stage? Mr. Tomofumi Nakamura of the Nishihira Honke’s Production Section replied to my simple query with a smile, saying “Then that would be rum, wouldn’t it?”

I did a bit of research and found out that strong alcohol made by fermenting sugar with yeast and distilling the substance is rum. The production method for Japanese shochu, on the other hand, is basically to attach kojikin mold to rice or barley in the first stage to make a primary mash. Then various types of shochu are produced. If sweet potato is added to the primary mash, you get sweet-potato shochu. If brown sugar is added, you get brown-sugar shochu. To my amazement, I learned that under the Liquor Tax Act the production of brown-sugar shochu is permitted only in the Amami Islands on condition that malted rice is used.

Koji mold is used in the second brewing stage as well, but steps are taken to accelerate the speed of fermentation.

Liquid brown sugar made by melting solid brown sugar

And then comes the third stage, in which brown-sugar liquid, made by melting solid brown sugar, is injected at last. “There it goes! There it goes! Yes, there it goes!” The fermentation progresses rapidly.

The sudden addition of brown sugar naturally intensifies fermentation much more than the reactionary process of koji mold converting the rice into sugar and then yeast fermenting the sugar into alcohol. The mash bubbles, as if joyously. While hearing the explanation, I could almost see the fermentation before my very own eyes.

The tertiary mash with liquid brown sugar added

The next process is distillation. It is this process that produces the difference between brews like Japanese sake and wine and distilled liquor. When properly fermented, the tertiary mash is distilled by placing it in a still. (After converting the mixture into vapor by heating, the vapor is returned to liquid form by cooling.) And after cooling and filtering, distilled liquor (shochu) with a high level of alcohol concentration is produced.

A still

Enamel tanks

Oak barrel storage

This distilled liquor is then put into storage for aging. Apparently products differ depending on the method of storage. At Nishihira Honke, depending on the product concept, the shochu is stored either in enamel tanks or in oak barrels. An example of a product that uses enamel tanks is Ki (brewed with white kojikin mold), and an example of a product that uses oak barrels is Amandi. “I must compare these products tonight!” I thought to myself, a sort of sense of mission (I’m exaggerating here!) welling up inside me.

Mr. Nakamura of Nishihira Honke’s Production Section (on right in photo) and brown-sugar shochu ambassador Mr. Sato (left)

Tasting Amami’s ocean blessings (izakaya Muchakana)

There are numerous restaurants serving local cuisine and brown-sugar shochu. Among the ones recommended by Mr. Sato, I chose the izakaya Muchakana as it seemed to have the best lineup of shochu. Incidentally, at first I thought the name of the izakaya was rather funny, because the Japanese word mucha means something like reckless or crazy. But later I found out that the name comes from the name of the heroine in a tragic folksong called “Mucha Kana Bushi.” Anyway, I hit the jackpot with this izakaya.

As well, of course, as the products of the Nishihira Honke distillery that I had visited, this izakaya had a wide choice of brown-sugar shochu; everything you could think of, really. And there was such a great selection of local food typical of Amami, I didn’t know which to choose. Anyway, to begin with, I ordered Nishihira Honke’s Ki and Amandi brown-sugar shochu, because I wanted to compare them and taste the difference. The Ki (brewed with black kojikin mold) was very easy to drink. While being really full-bodied, it had a refined aroma and slight sweetness. The Amandi, which had been stored in an oak barrel, had a deep richness and strong sense of aging. Maybe it would be good to drink leisurely on the rocks. Since both types would go down well with local fish sashimi, my mouth began to water.

As well, of course, as the products of the Nishihira Honke distillery that I had visited, this izakaya had a wide choice of brown-sugar shochu; everything you could think of, really. And there was such a great selection of local food typical of Amami, I didn’t know which to choose. Anyway, to begin with, I ordered Nishihira Honke’s Ki and Amandi brown-sugar shochu, because I wanted to compare them and taste the difference. The Ki (brewed with black kojikin mold) was very easy to drink. While being really full-bodied, it had a refined aroma and slight sweetness. The Amandi, which had been stored in an oak barrel, had a deep richness and strong sense of aging. Maybe it would be good to drink leisurely on the rocks. Since both types would go down well with local fish sashimi, my mouth began to water.

The first dish I ordered to go with my drink was local fish. I had heard from someone working at the fishing port that there had been no local fish catch due to stormy weather, but nevertheless there were local fish in my assorted sashimi serving.

In the photo of my sashimi serving, the top center fish is yellowfin tuna, and to the right of that is diamondback squid, which Mr. Sato had recommended due to its fleshiness and tastiness. Middle left is ember parrotfish (a member of the parrotfish family that inhabits the warm southern ocean) with sea grapes atop vinegar and miso dressing; middle center is sickle pomfret; and to the right of that is spotted knifejaw. And the fish in the forefront is local octopus, which is not influenced very much by stormy weather and is often caught.

When seen before cooking, the ember parrotfish, which is called erabuchi on Amami-Oshima, is colorful and looks like a typical fish of the southern seas. Compared with northern fish, it only has a little fishy aroma. For that reason, it is usually served with vinegar and miso dressing. I thought it was very tasty indeed. The sickle pomfret and spotted knifejaw were delicious too. Previously I had thought that southern fish were not so tasty, so my conventional thinking was upturned. The diamondback squid consisted of thick slices, but they were sticky and sweet, and the local octopus was softer than that eaten in Tokyo. I felt that the umami, or savoriness, was increased by the sweetish local soy sauce. Of course, by its cooking methods for the fish, that restaurant probably possesses some technique for bringing out the umami even in fish not caught that morning. It was a wonderful izakaya.

What next? As I was wondering what to order, a restaurant staff recommended tobin-niya boiled in salty water. Tobin-niya is strawberry conch (the Japanese name is magakigai)). Apparently the suffix –niya means shellfish in the local dialect. The strawberry conch hops around the coral reef sea floor with its claws, so hence the prefix tobin (from the Japanese word for hopping around, tobu). So tobin-niya literally means “hopping shellfish.” There was only a little flesh in the shell, which I pulled out using a toothpick. But when I ate it, the taste of coral reef spread inside my mouth. It was so delicious, my toothpick hand just wouldn’t stop going for more. Without a second thought, I ordered another helping.

What next? As I was wondering what to order, a restaurant staff recommended tobin-niya boiled in salty water. Tobin-niya is strawberry conch (the Japanese name is magakigai)). Apparently the suffix –niya means shellfish in the local dialect. The strawberry conch hops around the coral reef sea floor with its claws, so hence the prefix tobin (from the Japanese word for hopping around, tobu). So tobin-niya literally means “hopping shellfish.” There was only a little flesh in the shell, which I pulled out using a toothpick. But when I ate it, the taste of coral reef spread inside my mouth. It was so delicious, my toothpick hand just wouldn’t stop going for more. Without a second thought, I ordered another helping.

Another recommended dish was mozuku seaweed tempura. It had a good appearance, light feel, and not too oily taste.

Next I had pork miso using chunky Amami miso, which is a favorite dish of Mr. Sato. This is a perfect side dish for those who like their alcohol. Be it Japanese sake or brown-sugar shochu, the drinks are sure to flow.

The last dish in the “pork course” that I had begun earlier that day at Shimameshiya Kano was simmered pig’s feet. Usually I have an aversion to pig’s feet, but this was so good, the taste was firmly etched in my mind. The people of Amami certainly know how to eat pork well.

The last dish in the “pork course” that I had begun earlier that day at Shimameshiya Kano was simmered pig’s feet. Usually I have an aversion to pig’s feet, but this was so good, the taste was firmly etched in my mind. The people of Amami certainly know how to eat pork well.

Finally, the restaurant staff who had explained all the dishes that I had eaten that evening in detail lit up a grill on the table to cook local turban shell meat in its own shell. The taste of the shell meat was excellent, of course, but it was the appearance of the turban shell that was unforgettable. Unlike the turban shells that I had seen before, these shells had no spines. One of the delights of eating in an unfamiliar place is not only the taste but also the unique appearance of things.

Finally, the restaurant staff who had explained all the dishes that I had eaten that evening in detail lit up a grill on the table to cook local turban shell meat in its own shell. The taste of the shell meat was excellent, of course, but it was the appearance of the turban shell that was unforgettable. Unlike the turban shells that I had seen before, these shells had no spines. One of the delights of eating in an unfamiliar place is not only the taste but also the unique appearance of things.

I have introduced Amami-Oshima in two parts. The island has a strong image of marine sports, but this time my visit focused on its other attractions. Amami-Oshima can be enjoyed not only in summer, when the sun is shining brightly, but also on rainy days and when the sea is rough. The island has many attractions, including culture, nature, and cuisine. Why not visit and see for yourself? I will definitely be going again, hopefully when the wild birds, and especially the ruddy kingfisher, are there!

Cooperation

Shimameshiya Kano

Address 173-4 Shinokawa, Setouchi-cho, Oshima-gun, Kagoshima Prefecture 894-1741

Tel.: 090-8918-0259

Holidays: Tuesday – Friday (Please check, as longer holidays may be taken for agricultural work.)

Nishihira Honke Co., Ltd.

Address: 21-25 Nazefuruta-cho, Amami City, Kagoshima Prefecture 894-0016

Tel.: 0997-52-0059

Website: https://kokutou-shochu.com/ (Japanese site only)

Izakaya Muchakana

Address: 1F ASJ Building, 4-18 Nazekaneku-cho, Amami City, Kagoshima Prefecture 894-0031

Tel.: 0997-52-8505

Business hours: 17:00–23:00

Holidays: Irregular

Website: https://www.muchakana.com/ (Japanese site only)

Amanico Guide Service

Operated by: Yuinchu Co., Ltd.

Address: 455-10 Nazeasani, Amami City, Kagoshima Prefecture 894-0043

Tel.: 0997-58-7879

Website: https://www.amami-occ.com/ (Japanese site only)