Pilgrimage Experience in Tokushima Prefecture

Japan‘s Prayer: Part 1

Pilgrimage Experience in Tokushima Prefecture

The Shikoku Pilgrimage around 88 temples in the region where the famous monk Kukai (774–835), also known as Kobo Daishi, did his practice many centuries ago, has the meaning of both a journey of belief and, among young people, a journey of initiation into adulthood. In recent years many people have come to make the pilgrimage by bus or car, but the walking pilgrimage, similar to the original practice conducted by trainee monks and ascetics, remains popular among energetic retirees and young people. The walking pilgrimage also attracts foreign travelers, who see it as a relatively cheap and good way to have a deep cultural experience.

Kukai and the Shikoku Pilgrimage

Kukai was born in 774, and when he was young he studied at a university in the capital, in preparation for a career as a court bureaucrat. Kukai grew tired of studying, however, and at the age of 19 he began practicing to become a monk in the mountains of Shikoku. Subsequently he entered the monkhood, and in 804 he crossed over to Tang China as a student monk on a diplomatic mission. Kukai returned to Japan two years later, having studied esoteric Buddhism, civil engineering technology, medicine, and other subjects. In 816 he initiated the construction of a monastic complex on Mount Koya. After Kukai’s death, his disciples traced his footsteps and began a pilgrimage that was the prototype for the Shikoku Pilgrimage. In the Edo period (1603–1868), the Shikoku Pilgrimage became popular among ordinary people as well as monks.

Pilgrimage Dress and Manners

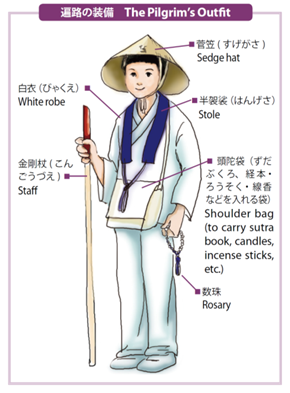

Beginning at Ryozenji in Tokushima Prefecture, the first temple and starting point for the Shikoku Pilgrimage, I experienced the walking pilgrimage. First of all, I went to a pilgrimage equipment store in front of the temple to procure the necessary things. The cartoon illustrates the full gear of a pilgrim, but as the photos show, actually people are free to go as they please.

The basic sequence and manners for worshipping at a temple are as follows: (1) At the temple gate, put your hands together and bow. (2) At the temple washstand, purify your hands and mouth. (3) At temples that permit it, strike the bell in the belfry. (4) At the Hondo (main hall), submit a card with your name, date, address, and so on written on it, offer a candle, incense stick, and money, and read a sutra. (5) At the Daishido (hall with a statue of Kukai), follow the same procedure as (4). (6) At the Nokyosho (sutra office), receive a stamp as evidence of your visit. (7) At the temple gate, turn back to face the temple, put your hands together, and bow.

Temples along the Shikoku Pilgrimage do not question a person’s religion and do not force you to accept the Kukai faith. Even if you are not a follower of the Shingon sect, and even if you are not Japanese, you can freely experience the pilgrimage and come face to face with yourself in the process.

Enjoying the Individual Temples and Pilgrimage Roads

One of the pleasures of the Shikoku Pilgrimage is that each temple has its own unique personality. The colors and shapes of the temple gates and main halls are different, but that is not all. Some temples have original gardens, or attractive surrounding scenery, or abundant types and numbers of Buddhist statues. Your interest will be piqued all the time.

Today, as the transport network has developed, most of the roads along the pilgrimage route are ordinary roads. Nevertheless, you will pass some old-fashioned pilgrimage paths as well. These are narrow paths where people used to walk across fields. When you walk along these paths, you feel a link with Kukai and others who treaded this way in the past, as well as the people walking now in front of and behind you.

Another surprising thing along the pilgrimage roads and at the temples is the hospitality that local people show to pilgrims. While researching for this article, I met people who walked for several kilometers with me between temples, showing me the way and directing me to places. And in the precincts of temples, people would give me handmade souvenirs. In this day and age, when human relations have become so weak, it was a rare experience indeed. At first I was a little confused, not understanding the sense of distance in human relations. But thinking about it afterward, it was perhaps the most memorable experience.

Reasons for Making the Pilgrimage: Memory of the Deceased and Initiation

At the lodging of the 6th temple, Anrakuji, I spoke with the chief priest, Shuho Hatakeda.

Q: What is the main reason why people make the pilgrimage?

A: The most common purpose is to pray for the souls of family members. People make the pilgrimage in memory of deceased loved ones, such as parents, a spouse, or a child. There are also people who go around the temples to pray for recovery from illness or something. Completion of the pilgrimage to all 88 temples is called kechigan [fulfillment of the pilgrimage].

Q: Young people seem to see it as a journey of self-discovery.

A: Kukai was 19 years of age when he first began practice in Shikoku and went walking. It was a journey of self-discovery for him as well. So the Shikoku Pilgrimage and the initiation of young people into adulthood go very well together.

Q: The Shikoku Pilgrimage is not necessarily religious. There is a strong tourist aspect as well, isn’t there?

A: Japanese Buddhism has a very tolerant religious view. It developed by adding Buddhist philosophy to primitive nature worship. So from a tourist perspective, it’s fine if people just feel lighter or better after the pilgrimage. But please do not forget that at the time of Kukai and other ascetics, it was an extremely harsh practice indeed. The pilgrimage roads were steep, and there was no food. The hospitality toward pilgrims arose out of sympathy for people who were making this tough journey.

Q: Do many foreigners make the pilgrimage?

A: Many foreigners, especially from Europe and North America, make the walking pilgrimage because they have a deep interest in Japanese culture. Rather unusually, the other day a group of Russians stayed here, and we had a discussion for about two hours after dinner. They said that in Russia at the moment there is a yearning for a return to natural religion and a lot of interest in the Japanese religious view.

All Kinds of People Walking

I walked in the reverse direction from the 17th temple, Idoji, to the 13th temple, Dainichiji, and on the way I encountered all kinds of people.

I walked in the reverse direction from the 17th temple, Idoji, to the 13th temple, Dainichiji, and on the way I encountered all kinds of people.

Shinsho Hirano, from the Shingon sect Daikokuji temple, had walked all the way from Kagoshima Prefecture—a real trainee monk! “I walked 65 kilometers a day,” he said, “so it didn’t take that long.” The usual traveling distance for walking pilgrims is 30 kilometers a day, so he was going at more than double that speed. And after the 1,200-km Shikoku Pilgrimage, he said, he was going to walk back to Kyushu!

Shiro Sakata from Hyogo Prefecture explained that he was doing the walking pilgrimage to commemorate his retirement and in memory of his deceased wife. His fresh smiling face was very impressive.

Shio Nakajima from Fukuoka Prefecture was 26 years of age. He had quit his job in a restaurant, where he had worked for three years, and was having a go at the walking pilgrimage while touring Japan by bicycle. When I asked him about his future plans, he answered clearly, “I want to do organic farming and run a restaurant using vegetables grown without any agricultural chemicals.”

Shio Nakajima from Fukuoka Prefecture was 26 years of age. He had quit his job in a restaurant, where he had worked for three years, and was having a go at the walking pilgrimage while touring Japan by bicycle. When I asked him about his future plans, he answered clearly, “I want to do organic farming and run a restaurant using vegetables grown without any agricultural chemicals.”

Klaus from Germany completed the Shikoku Pilgrimage last year in about 50 days, and this was his second time. “Last year I lost my wallet during the trip,” he said. “Somebody found it and, wanting to return it to me, delivered it to the next temple. I knew there was no need to check the contents. There wasn’t likely to be anything missing. That’s the Shikoku Pilgrimage.” When I asked whether he would recommend the pilgrimage to others, he thought for a moment and then replied, “Although I don’t speak Japanese, I like Japanese culture and have a good understanding of the Japanese people, so there is no problem at all. But maybe it’s a tough journey for people who don’t have much interest in and understanding of Japanese culture and don’t like inconvenience.”

“Last year I lost my wallet during the trip,” he said. “Somebody found it and, wanting to return it to me, delivered it to the next temple. I knew there was no need to check the contents. There wasn’t likely to be anything missing. That’s the Shikoku Pilgrimage.” When I asked whether he would recommend the pilgrimage to others, he thought for a moment and then replied, “Although I don’t speak Japanese, I like Japanese culture and have a good understanding of the Japanese people, so there is no problem at all. But maybe it’s a tough journey for people who don’t have much interest in and understanding of Japanese culture and don’t like inconvenience.”

The Shikoku Pilgrimage is a journey of self-discovery and, especially the walking pilgrimage, an encounter with others. I think I understand why people head for Shikoku when they reach a milestone or turning point in their lives or feel a sense of impasse or whatever.

For foreign tourists, bearing in mind Klaus’s advice, walking in Shikoku for a few days will lead to a deeper understanding of Japanese culture. Guides with maps, written in English, Korean, and unsimplified and simplified Chinese, are available at the first temple, Ryozenji. The following websites might be useful as well.

- Category

- Culture、Culture、Experiences、News、Travel